KAJ FRANCK

(9.11.1911–26.9.1989

1

CHILDHOOD AND FAMILY BACKGROUND

Kaj (Gabriel) Franck was born in Vyborg on 9th November 1911. His father, Kurt, was a descendant of a Lübeck mercantile family, while his mother, Genéviève, was the offspring of artistic, Swedish-speaking Finns. Franck's maternal grandfather, architect and writer Jac. Ahrenberg, also worked in industrial art, for example as the Arabia factory's first designer. Trained in furniture design, Genéviève was partly responsible for the design style of Franck's home, which he described as 'cubist Viennese art nouveau' . The family spent its summers in Antrea, Leppäniemi, were Franck first encountered a simple peasant culture. Upon the death of Kurt Franck, when Franck was just seven, the family moved to Helsinki. There, Franck spent seven years in secondary school, before entering the furniture design department of the Central School of Craft and Design, from which he graduated in 1932.

Kurt Ekholm and Kaj Franck.

Kurt Ekholm and Kaj Franck.

2

INFLUENCES

Franck studied Finnish art and design during turbulent times. His work is marked by the period's heated exchanges of opinion, both for and against functionalism. In 1930, he attended the famous Stockholm Exhibition, which represented the Nordic breakthrough of functionalism. However, he did not adopt functionalist principles in his own work until the socially and economically challenging period of post-war rebuilding, in the late 40s.

At Arabia, Franck continued the work begun in the 1930s by Kurt Ekholm (1907–1975), as a designer of functional everyday objects. He then joined an international group of designers devoted to redesigning mass-produced consumer goods, with a modern aspect and meeting societal needs e.g. by rejecting an ornamental, decorative approach. Franck's forebears in this regard were figures such as the Swede Wilhelm Kåge (1889–1960), designer for Gustafsberg, the German Wilhelm Wagenfeld (1900–1990), designer for Bauhaus and the Americans Mary (1905–1952) and Russel Wright (1904–1976).

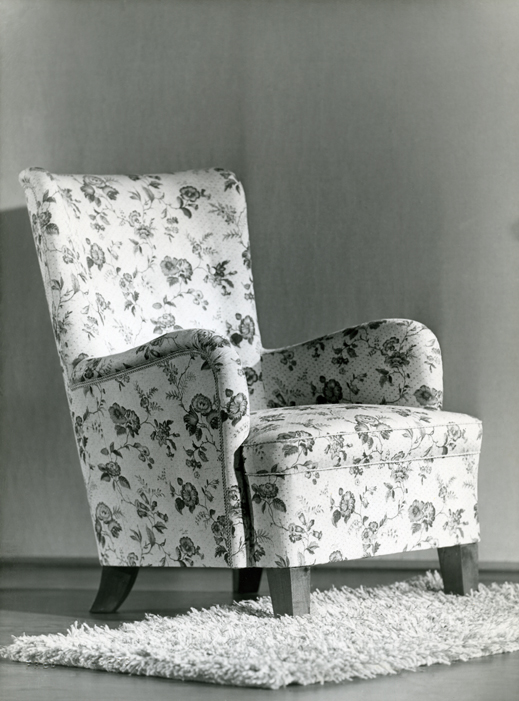

Kaj Franck / Ab Hemflit-Kotiahkeruus Oy, Armchair 1937. Photo Fred Runeberg.

Kaj Franck / Ab Hemflit-Kotiahkeruus Oy, Armchair 1937. Photo Fred Runeberg.

3

TEXTILE AND FURNITURE DESIGN

In the 1930s, Franck designed a few covered armchairs representative of the period's soft functionalism, while working for the interior decoration businesses Te-Ma and Hemflit-Kotiahkeruus.

From 1940–1945, Franck worked for the firm Helsingin Taidevärjäämö. Here he used narrative elements on printed fabrics – something shunned by representatives of functionalism. Independently Eva Taimi, who joined Taidevärjäämö in 1937, and Franck designed models, aiming to develop the firm into a high-level industrial art company. Taimi produced clean and working drawings of Franck's models. From 1947 to 1948, Franck designed a few stylised plant motifs for the Artek collection.

4

FIRST GLASS OBJECTS

In 1946, Franck participated in Iittala's glassworks design competition, whose aim was new engraving models and glasses for a Nordic arts and crafts exhibition to be held in Stockholm. First prize went to Tapio Wirkkala, with Franck taking second and third prize. Among the submissions was an engraved decanter designed by Franck. He designed his first bubble glass objects in the same year. These became the trademark of his glass objects designed for Iittala.

In September 1948, at a small industrial art exhibition held at the Stockmann department store, the Tupa collection was introduced. This set was blown from green glass, to a design inspired by 'time-honoured Finnish glass' traditions.

Kaj Franck /Iittala, Tupa 1948. Photo Rauno Träskelin.

Kaj Franck /Iittala, Tupa 1948. Photo Rauno Träskelin.

5

FIRST MODELS FOR ARABIA

Franck's first task for Arabia was to redesign the mixing bowl for the firm's stackable objects. He was also involved in design for the ARA department's production, creating a few jugs decorated with a plant motif.

Prior to Kilta, Franck designed articles such as the RNA coffee and tea set, sold from 1949. A collection of innovative coffee and tea jugs arose from his B model in 1949–1951, in which he explored the potential of casting techniques for tinted porcelain and faience mass. Some of these jugs were in production until 1970, under the model designations RN, RNA, FL and KF. Although round in shape, these articles already bear the hallmark of the developing Kilta look. In these jugs, Franck seeks a minimalist form and mass production aesthetic.

In the post-war period, to assist households the Finnish Family Federation (Väestöliitto) commissioned dishware packages from Arabia. These were formed through a method typical of the time, by using decoration to combine parts from ready models into a single whole.

Kaj Franck / Arabia, Sointu RN 1949. Photo Rauno Träskelin.

Kaj Franck / Arabia, Sointu RN 1949. Photo Rauno Träskelin.

6

KILTA

In many ways, Kaj Franck's slogan 'smash the dinnerware' aptly describes the radical design mentality and unconventional requirements from which the Kilta collection emerged. Franck began designing Kilta in 1948, during the height of the post-war housing crisis. With their light-coloured surfaces and minimal dimensions, modern dwellings fulfilled the ideals of Finnish modernism, which also provided the impetus for the design of Kilta.

With no training in ceramics, Franck solved the design issues purely on the basis of function and form. The result was pared-down shapes and sparing use of colour. The key insight behind Kilta lies in the objects' compatibility. They also had to match old dishes, or dishware in production.

The Kilta collection of 1958 included 37 loosely combinable items. As well as white, the colour range included black, blue, green and yellow.

Kilta entered the market in 1953 and production ended in 1974.

7

COLLABORATION WITHIN ARABIA

Franck headed Arabia's model design department from 1946 to 1961. There, he and Saara Hopea shared a workroom; with Kaarina Aho and Ulla Procopé working next door. Franck, Hopea and Aho formed both an exhibition design group and a project team. On this basis, they supervised the illustration of Wärtsilä's products and held product presentations for salespersons and general audiences. Aho and Procopé created the decoration, particularly for objects new to production.

Kilta's sister setting, the B model, began to retail in 1953. These pieces retained soft shapes, their silhouettes casting a varied, wavy outline. Aho was given the task of designing the later pieces for the B-model, focusing on exploiting the potential of the decoration approved for the cup's surface.

The B model's decoration is exceptional, being the Arabia factory's first instance of decoration under glazing. Polaris, Linnea and Pyrola, all by Raija Uosikkinen, are the best-known of the B model decorations.

Kaarina Aho, Saara Hopea, Ulla Procopé and Kaj Franck.

Kaarina Aho, Saara Hopea, Ulla Procopé and Kaj Franck.

8

JAPAN

Franck first visited Japan in 1956, studying Japanese art and gardening. Surprisingly critical in places, he could also see what was unique and valuable in Japan. He described the Zen temple and garden of Ryōan-ji as "perhaps the most beautiful I have ever seen."

He was enchanted by cast-iron, which plays a special role in Japanese tea services, as well as ceramics, wood and textiles. Form and surfaces were decisive. His characteristic minimalism and distaste for waste and extraneous detail chimed in with the interiors, sensitive Japanese awareness and respect for materials.

9

FUNCTIONAL FORM AND DESIGNER RESPONSIBILITY

During the 1960s, Franck crystallised his concept of designer responsibility. He took a radical approach, emphasising the designer's role in advancing social values, ethics, aesthetics and anti-materialism.

He was a critic of 'design for design's sake' i.e. that the aim is always a new product. In the face of the growing waste problem created by industry, he began to talk about material recycling. Ideally, he believed that products should be designed from material which disappears without trace after use. As a prime example of a 'functional object', he often cited the traditional Kalakukko dish (fish inside a loaf) of Finland's Savonia region. This functions both as a storage container and the meal itself, with zero waste.

In his own design, designer responsibility can be seen in the fact that, while respecting traditional models, he sought as few solutions as possible that would become 'dated'.

10

GEOMETRICAL – UNIVERSAL FORMS

Franck emphasised the universality of basic geometrical forms, such as the sphere, cube, cone, cylinder and ellipse. These formed the basis of his design. He articulated them into forms common throughout the world and owned by no one. For example, he gave prominence to the classic semi-spherical tea-cup.

Franck also referred to popular objects refined through time into practical forms, which have served their owners from one century to the next and whose designer is neither known nor sought after. Examples of this could be found in Japanese material culture, for example.

11

SAARA HOPEA AND KAJ FRANCK

Collaboration between Saara Hopea and Kaj Franck, which continued until 1960, began in 1946 when Hopea was still a student of Franck's at the Institute of Industrial Art. During the 1950s, Hopea and Franck redesigned both the products and packaging of the Nuutajärvi Glassworks' product range. Franck and Hopea's cooperation was made fruitful and easy by the similarity of their functional glass design principles.

Their cooperation for Wärtsilä led to the firm's first independent gallery and sales showrooms, designed in 1951 and located on Helsinki's North Esplanade.

Wärtsilä's first independent gallery and sales showrooms, located on Helsinki's North Esplanade. Photo Pietinen

Wärtsilä's first independent gallery and sales showrooms, located on Helsinki's North Esplanade. Photo Pietinen

12

ON MATERIALS

In a lecture given in 1967, Franck stated the following about materials: "To a maker of functional objects, material is an assistant, a servant that compensates for our own shortcomings." Although interested in materials and their combination, their use was not to be an end in itself. He did not view materials themselves as differing in value. Franck combined wood and metal with glass and ceramics, while proposing that less-valued materials, such as enamel and plastic, be combined with table settings. However, he did not accept Arabia's sales department 's idea of putting the sleek-lined Kilta together with cane trays. During the 1950s, he also explored the combination of ceramics and plastic, as well as possible applications for paper.

13

GLASSWARE

As well as ceramics for Arabia, the task of the Nuutajärvi Glassworks was to produce glass for sale. When Franck joined the Glassworks, it was in sore need of new glassware for production, in response to buoyant ceramics markets in Europe and the USA. In addition, Arabia had a virtual monopoly over sales to homes and restaurants in Finland. During Franck's entire time at Nuutajärvi, both blown and pressed functional glass product lines formed a core part of his design work.

14

COLOURED GLASSWARE

Colours, originally used to cover impurities in the moulded glass mass, became a kind of trademark of the Nuutajärvi Glassworks. Because colours vary depending on the quality of glass, the factory had separate colours for blown, pressed or art glass. In blown glass, the colour could vary according to the glass's thickness. Colours are intensive in thick pressed glass. Due to the development of new colour options, as well as production techniques and the glass masses used, colours changed over the years.

In 1953, under product number 5023, Nuutajärvi introduced a new, multicolour glass product line. This was a success both in Finland and the USA.

Franck could experiment more freely with various colour combinations in art glass objects, in which more expensive, so-called tap colours could be used.

15

BLOWN GLASS – PRESSED GLASS

Upon becoming Nuutajärvi's glass designer, Franck decided to broaden the range and raise the level of the factory's functional glass. He was particularly interested in pressed glass, since it enabled cheaper production than blown glass. In addition, he viewed the limitations of pressed glass techniques as a challenge.

Franck also sought to lower the production costs of blown-glass serial products. This was an important basis for the design of the handleless pitchers of the 1950s, for example.

16

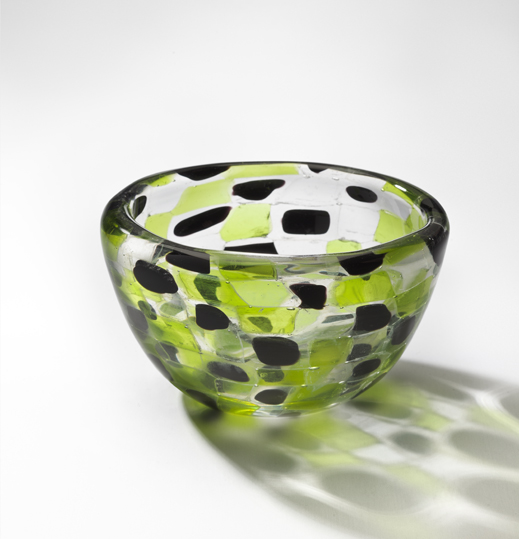

ART GLASS

Franck joined the Nuutajärvi Glassworks to continue the work of the undisputed groundbreaker in Finnish art glass, Gunnel Nyman (1909–1948). The younger man's development interests found fertile ground in Nyman's thick, clear, optically brilliant cut objects, and her technique based on air-bubbles.

While developing art production, Franck's creative energies were maintained by his quest for beauty and his personal curiosity. The result is a unique blend of rich colours and textures, often combined with the simplest of forms.

Kaj Franck / Nuutajärvi, Bowl 1960s. Photo Rauno Träskelin.

Kaj Franck / Nuutajärvi, Bowl 1960s. Photo Rauno Träskelin.

17

ARTIST'S RESPONSIBILITY

"A product line signifies shared responsibility for decor objects. For unique art objects, the situation is quite different; an individual, industrial art object produced from raw materials is as much a work of art as any painting or sculpture. Its intrinsic value is not tied to the practical purposes behind it. It is also the utterly unique outcome of the artist's subjective appreciation of beauty, and his or her creative impulses, its sole purpose being to convey the pure, aesthetic values it harbours within. Another aspect of its uniqueness lies in the fact that, recreated, it can never be exactly the same. Born only once, a unique art object is the responsibility of only one person, the artist."Kaj Franck, Anonymiteetti, Keramiikka ja lasi 1966 (Anonymity, Ceramics and Glass 1966).

Franck sourced traditional techniques when designing art glass. These he developed and adapted, while also using his own 'free-play' approach, which is akin to the glass ring technique.

18

SUCCESSFUL EXPERIMENTS

Whether for art glass or more mundane everyday drinking glasses, continuous exploration and exploitation of new techniques, and of the optical possibilities presented by glass material, formed a core part of Franck's glass design.

By thinning the mouth of the glass or through bevelling, for example, Franck sought various optical effects in tableware. As a result of his experiments with art glass colours and techniques at Nuutajärvi, many previously familiar techniques were revived and new ones developed, such as the colour ring technique developed in the 1960s. Under Franck's leadership a new method was developed for the production of traditional air filigree, cased glass and filigree glass.

19

ANONYMITY IN DESIGN

In the mid sixties, the idea of anonymity with respect to industrially produced functional objects inspired a lively debate. In 1965, the Nuutajärvi Glassworks announced that it would cease using designers' names in conjunction with mass-produced commodities. This was based on the idea that the designer was putting his or her name to products for which he or she could not solely claim the credit or, in negative cases, be blamed. The Glassworks' Artistic Director, Kaj Franck, lay at the centre of the controversy. At the beginning of the sixties he had already given some trenchant opinions on too much attention being paid in product marketing, and the related copy, to designers instead of products. In a 1961 edition of the magazine Kaunis Koti (Beautiful Home) he stated: "A serial production design should not be one of which people grow tired. It should be so relevant that it 'lasts' for years and decades, and so unobtrusive that the user doesn't start to wonder who designed it. The factory's mark should suffice as the producer's name."

The Nuutajärvi Glassworks resumed using the designer's name in marketing in the 1970s. Franck too turned his back on his anonymity concept.

20

TEACHER

As an instructor of design drawing and stylistics at the Institute of Industrial Art from 1945, Franck maintained contact with young designers. In 1960, his authority among the younger generation grew when he was appointed Artistic Director of the Institute. Bauhaus formed the theoretical basis of a mandatory foundational course.

In everything he taught, Franck clearly sought to convey the richness and multiform nature of solutions. Bauhaus theory's influence on style was among the foundational course's assignments: point, line and surface i.e. the A, B, C of the abstract approach. Design meant something very different to mere drawing-based composition. It can perhaps be defined by 'arrangement' – the development of ideas and thoughts.

Basic course of general design, in 1977.

Basic course of general design, in 1977.

21

NATURAL FORMS

Franck was fascinated by the entire human environment, from knives and dishes to the broader landscape. A garden was as much a place of work as a scene of leisure pursuits – Franck viewed it as comparable to a glass workshop. For him, it was an aesthetic practicing ground. Here, he could perform compositional experiments and meditate on the essence of forms and colours. This was the setting in which he sought the origins of form.

"In functionally beautiful objects, I see a close relationship with natural forms: the economic structure of an egg, a seed capsule, the structure of internal organs, organic forms and systems, not to mention the geometrical, clear crystal structure of stone or a gully eroded into a gently sloping landscape."

Through small-scale, garden experiments with stones, moss and vegetation, Franck sought to demonstrate that people and nature can co-exist on mutually agreeable terms, but that this would require considerable commitment from humans. In the rock garden of the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture, you can still gain first-hand experience of Kaj Franck's message as an artist and man.

Kaj Franck,Sketch for wallpaper or fabric called Vårlök.

Kaj Franck,Sketch for wallpaper or fabric called Vårlök.

22

DESIGN IN THE 1970s AND 80s

During these decades, Franck had the opportunity to devote himself to long-cherished ideas, developing new product lines from old products. The nub of this design philosophy was crystallised by these. Luna, a pressed glass collection and Purtilo, a vase, bowl and drinking-glass set, were redesigned and assembled from glass objects already in production.

The Pitopöytä plastic collection, which entered the markets in 1978, fulfilled Franck's long-standing dream of giving this underrated material a place in its own right alongside traditional materials used for dishware and cutlery.

In 1979, upon being invited to design the Teema collection on the basis of Kilta, he gained an opportunity to rectify his 'mistakes' in Kilta. The technical design of each product had to begin from scratch, owing to the difference between the production process for stoneware and faience. He chose off-white stoneware as his material.

23

FRANCK'S LEGACY

Franck's dictum that products should have timeless, multipurpose forms can be seen in many products, still being made today, which have become symbols of modern Finnish design.

Some product lines have begun to live a life of their own. Only the original design concept remains of Franck's contribution to the Teema collection, which has been altered to meet modern needs. Of the five colours ultimately used, only white was part of Franck's design. Franck's legacy also lives on in Arabia's products, such as the 24h, ABC, KoKo, Oma and Nero.

Kristina Riska, Kati Tuominen-Niittylä / Arabia, KoKo 2005. Photo Rauno Träskelin.

Kristina Riska, Kati Tuominen-Niittylä / Arabia, KoKo 2005. Photo Rauno Träskelin.